A pragmatist’s guide to zero-emission logistics

Originally published at the WEF Agenda blog on January 17th, 2019

This article is part of the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting

- Sustainable trade will require the participation of emerging economies.

- Finding the right balance between sustainability and economics is crucial.

- The technology exists; the real barrier is changing existing mindsets.

- Eliminating avoidable emissions is a good starting point.

Getting to zero emissions in logistics is a daunting prospect. Developing zero-emissions fuels and vessels is a critical pathway forward, but this approach has its limitations. In a cost-driven industry, a high-cost, high-risk focus on zero-emissions technology may position many players in emerging markets as part of the dirty past – not the clean future. We need a pragmatic approach that balances high-tech practices with practical ones that offer a role for everyone. We can reduce avoidable emissions through more efficient supply chains, but we need to shift mindsets. That’s where we should take immediate steps while continuing the longer journey.

Without the willing participation of emerging market players, a sustainable future for global trade is at risk.

Trade is growing most and fastest in emerging markets, with the growth of import volumes into Asia’s emerging markets as an example. In 2018, developing economies accounted for 64% of seaborne trade. Engaging this majority of actors is essential for the success of the zero-emissions project.

At the same time, we need to balance the environmental with the social and economic aspects of sustainability. If we require investment in new vessels and bunkering infrastructure to participate in global value chains, some actors will simply not comply, and will be left out – and if a port or a country is left out, so are its small and medium-sized firms (SMEs). For SMEs in these markets, accessing global value chains is critical to achieving stable growth and creating jobs. Keep in mind that SMEs contribute over 50% to GDP and account for two-thirds of formal employment in many countries.

Even in mature markets, the largest industry players can’t agree on who should cover the cost of transitioning to a zero-emissions logistics industry.

Logistics is a highly cost-sensitive industry. Just consider that second-generation biofuels are commercially viable, but not available, because no one is yet willing to consistently pay higher costs to ship goods. When given a chance, only a handful of shippers choose the environment over cost. The industry consensus is that a global fuel levy will be necessary to incorporate the social cost of carbon into fuel costs – but action on this has stalled, because oil companies don’t think it’s fair that they shoulder most of the cost burden, even if that cost is ultimately passed on.

Will emerging markets be able to afford the transition to cleaner fuels?

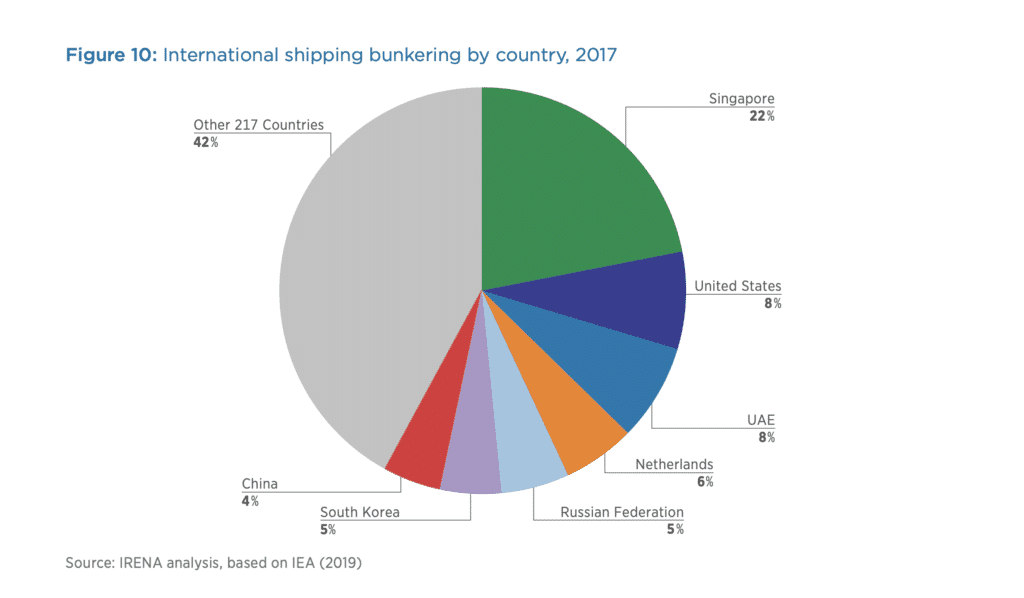

Transitioning to new fuels will be expensive in the short term. Recent research by the Global Maritime Agency – due to be published in late January – estimates that out of up to $1.9 trillion in investments needed to fully decarbonize maritime shipping by 2050, only 13% is for ships. The remaining 87% would be for land-based infrastructure and production facilities for alternative fuels. The International Renewable Energy Agency says “any shift toward a cleaner sector will require important changes to port terminal infrastructure and operational equipment [see chart below], as well as daily operational practices”.

Image: IRENA

Consider coastal African countries, or Viet Nam, where newly-discovered offshore oil resources have the potential to drive considerable growth. How should these countries consider these potential assets in a zero-emissions future? Should they not plan to benefit from their natural resources? Should they, instead, invest in port infrastructure for zero-emissions fuels that they will likely need to import? Is that fair?

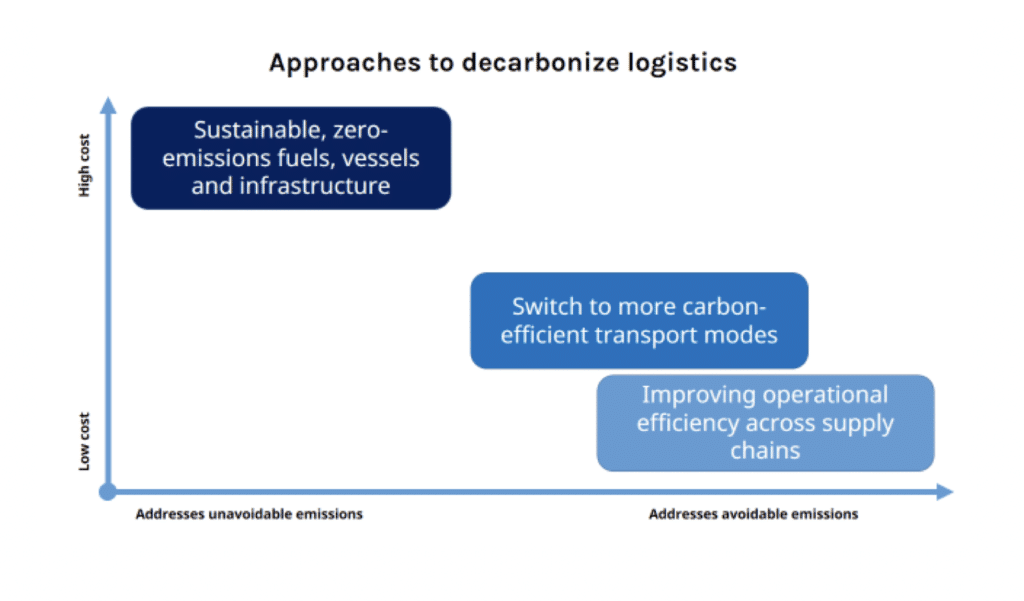

The industry should mobilize around practical, system-level approaches to address avoidable emissions across supply chains.

No matter what the fuels of the future will be, it will be useful to reduce the total amount of fuel needed to power global trade. More fuel-efficient transport modes, supply-chain optimization and operational efficiency should be prioritized for their emissions-reducing potential. These solutions are not, and cannot be mode-specific, but must address global logistics as a system.

Image: Authors / IRENA

To address avoidable emissions, data-informed optimization across modes and supply chains deserves more industry attention.

Avoidable emissions are embedded into inefficiencies at every step along the supply chain. It’s tough to measure their contribution to overall transport emissions, but the share could be substantial. Consider that in many markets, sometimes more than 40% of trucks on the road at any given time are moving empty, and a much greater percentage are underutilized.

Beyond individual shippers or supply chains, optimization across the logistics system makes better use of transport assets across a country’s distribution network, or back and forth along a trade lane. On a global scale, the containerization of US agricultural exports addressed the asymmetry of cargo flows between the US and China. Digital freight booking platforms, like Cargo X in Brazil, can drastically improve asset utilization, reducing trips, kilometres, costs and emissions. In the US, when Ocean Spray and Tropicana, two fruit juice competitors, collaborated to enable sharing of empty refrigerated rail boxcars, both parties reduced transport costs, and Ocean Spray’s emissions were reduced by one-third.

The barrier isn’t tech. It’s mindset. How do we shift it?

Logistics is full of myriad actors with high levels of interdependence and competing interests, and this drives down costs. Fierce competition leads to such low prices in road freight that often it is cheaper to send a dedicated truck less than half full than it is to use a small freight carrier. From this baseline, how can industry players work together – in ways that preserve competition – for incremental environmental gains?

First, emissions should be a measured key performance indicator against which supply chain performance is evaluated. For example, some shippers have instituted an internal carbon price. Other sustainability performance rankings can help, both internally and for third-party service providers, but we must be careful to avoid the proliferation of varying questionnaires, and include incentives to improve environmental performance. Immediate exclusion of carriers that can’t meet high environmental standards won’t shift behaviour, and may bankrupt smaller players.

Second, we need to amplify the message about the business case. Logistics services providers can use their visibility across supply chains to identify collaboration opportunities and estimate cost and emissions savings, so shippers can visualize lost value. We all must be retrained and our data systems redesigned to actively look for these opportunities. When collaboration is successful, we need to transparently communicate these stories to clarify what’s possible and set higher environmental aspirations.

Reducing avoidable emissions alone won’t get us to zero. But this approach is open to everyone everywhere, starting now, and it can save fossil fuels in the present, and open the door to zero-carbon fuels in the future.